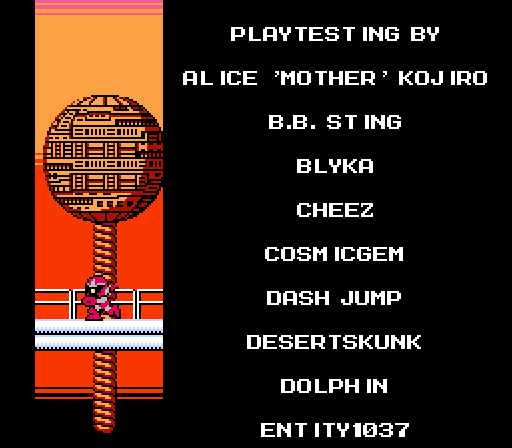

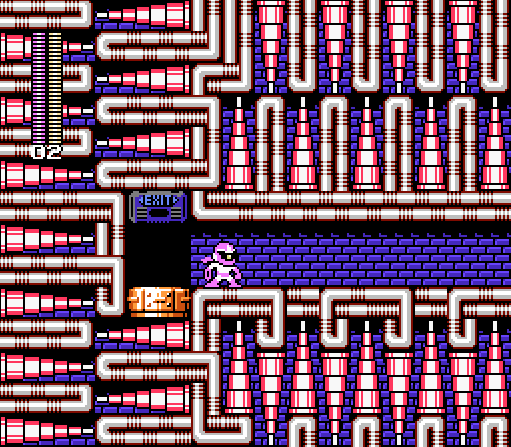

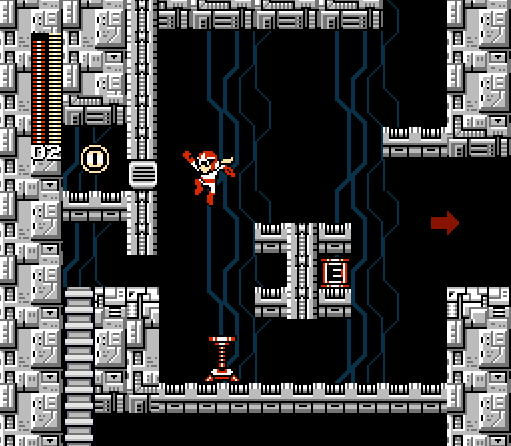

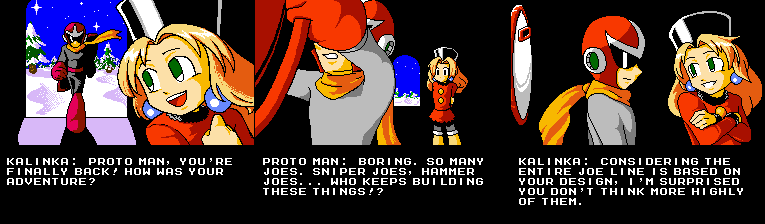

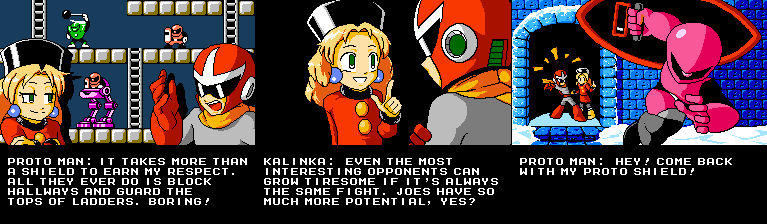

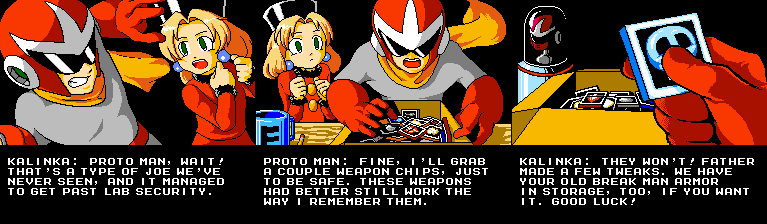

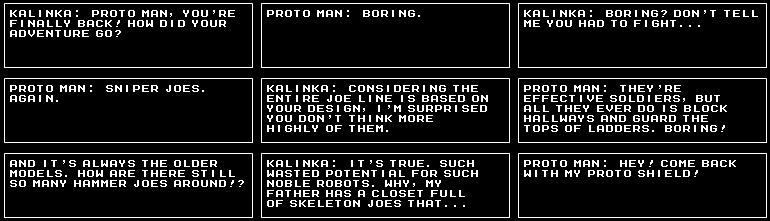

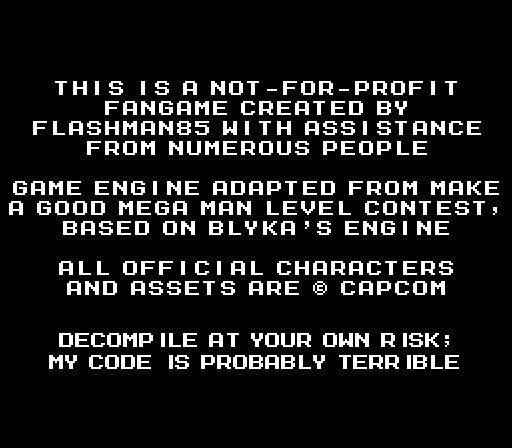

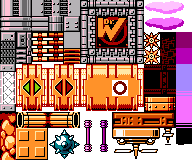

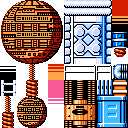

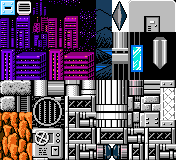

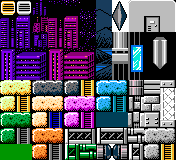

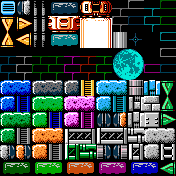

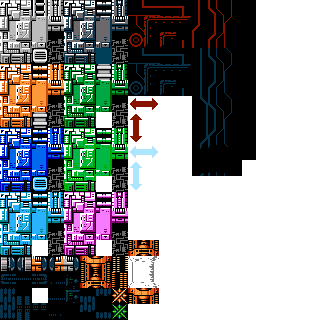

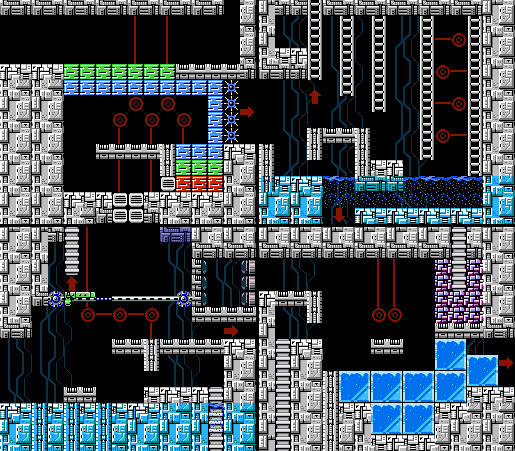

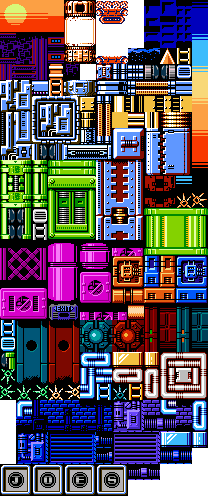

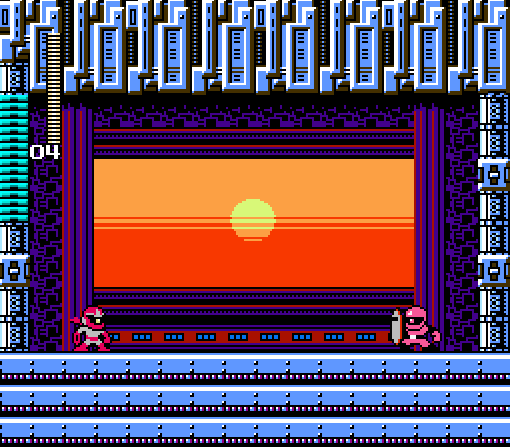

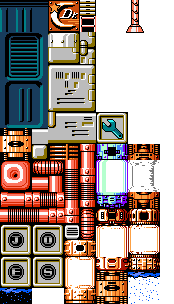

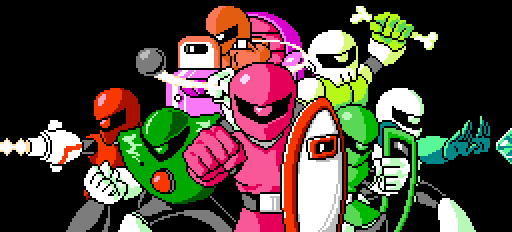

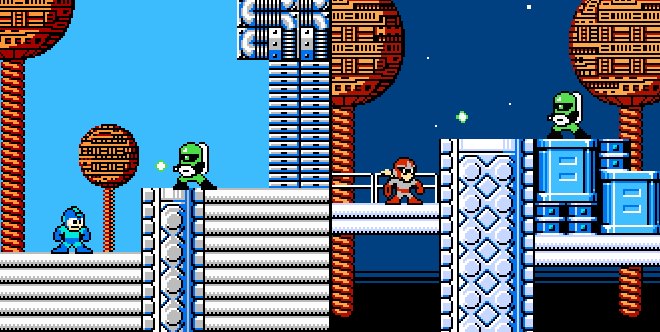

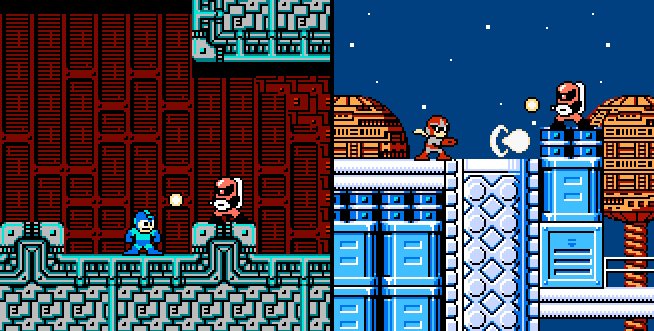

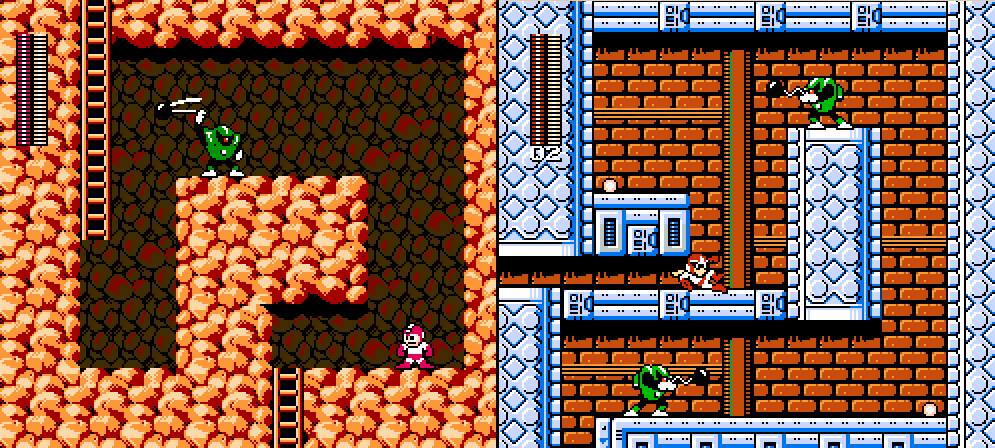

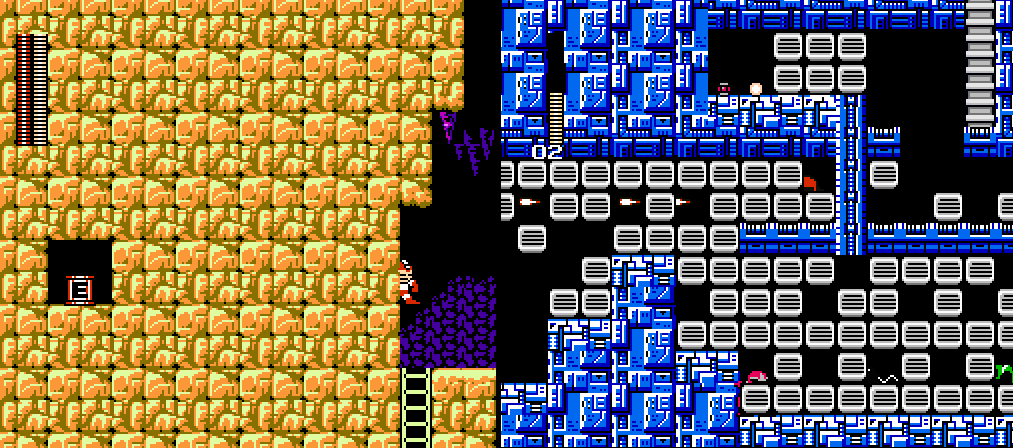

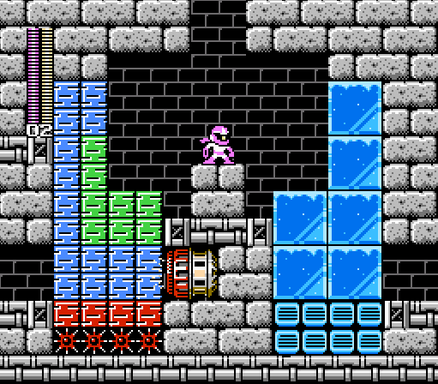

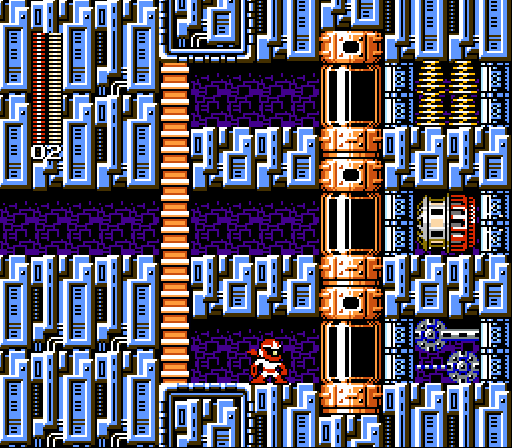

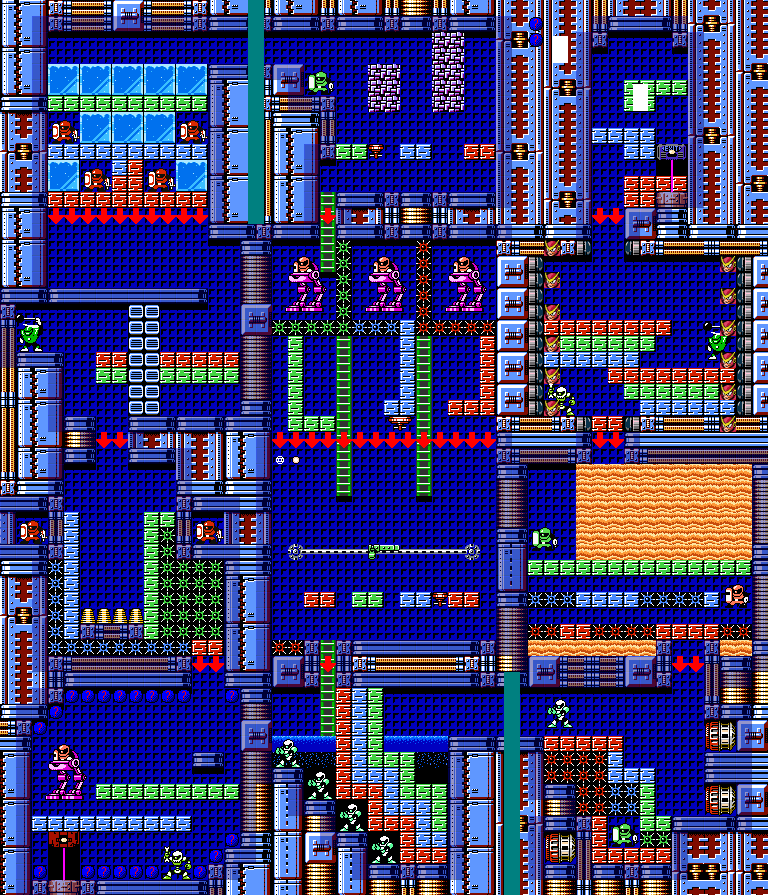

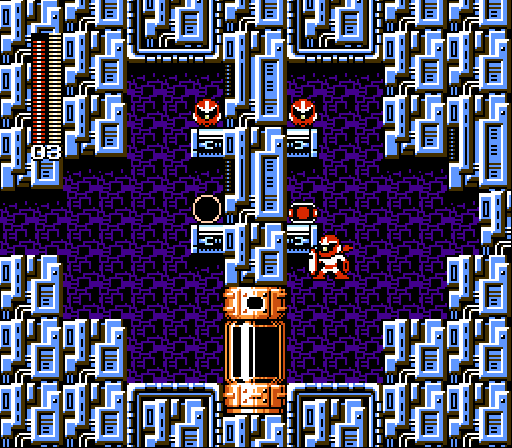

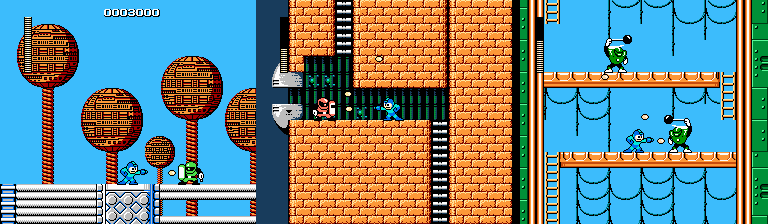

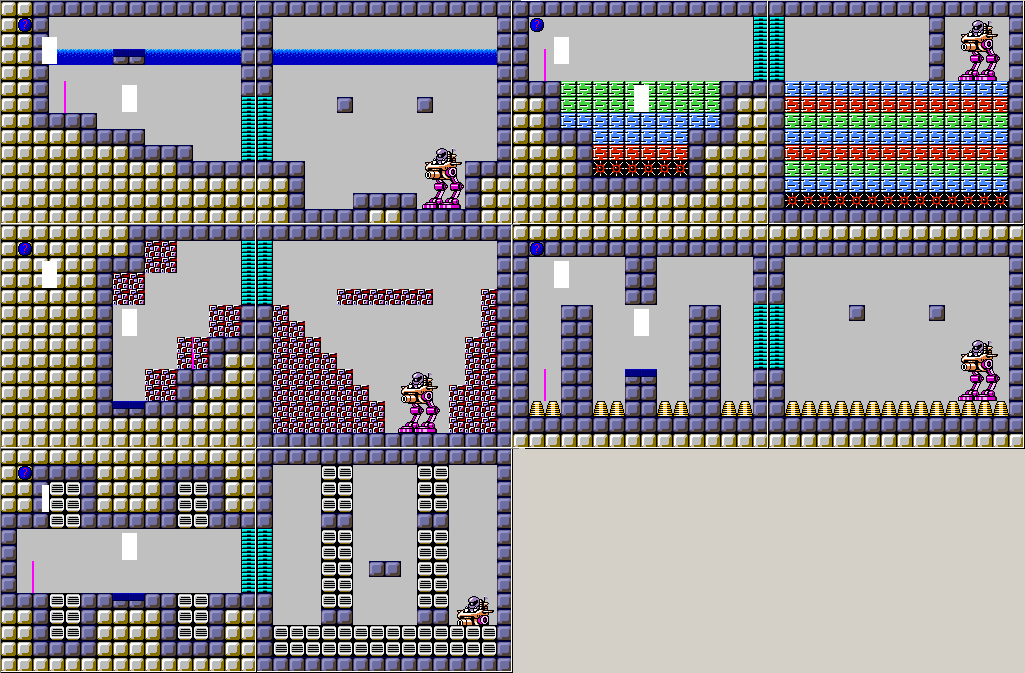

Two years. That's how much of my life I devoted to nurturing OH JOES! from some goofy level concept into a full-blown game with original cutscene artwork, an original soundtrack, 58 randomized disclaimers for the startup screen, 500 words of dialogue, 1500 words of game over hints, multiple language options, multiple paths, multiple difficulties, multiple playable characters, and plenty of Easter eggs. I participated in every aspect of development—planning, spriting, programming, level design and decoration, music composition, writing, translating, and playtesting—learning any necessary skills along the way, including skills that hardly come naturally. Overcoming my aversion to collaboration, I coordinated with 34 people to make the game better than it ever would have been as a solo project. To me, OH JOES! isn't just another Mega Man fangame; it's a remarkable accomplishment that pushed me out of my comfort zone and helped define an entire chapter of my life.

At first, the game was a fun distraction, something I worked on a few times a week for a couple of hours at a clip. After a year, it was a pleasant obsession, consuming as much of my free time as my sanity (and my wife, friends, and family) would permit. By the last few months, OH JOES! was more of a burden than a joy, an obstacle between me and how I wanted to be spending my life, but I was committed to doing it right.

The good days, of which there were many, were the ones in which I conquered some programming problem myself, designed some challenges I felt good about, had productive interactions with the other people involved in the project, incorporated lots of playtester feedback, or finalized basically anything (menu screens and sprites were especially gratifying). I took it as a very positive sign that I frequently found myself humming the soundtrack, and that I didn't get sick of fighting Joes until the last few months—which, considering the impetus for the project, is rather astonishing. When I posted updates on social media, I could rely on at least a few (if not several) supportive responses to validate my work and keep me excited about continuing.

The bad days, which became more frequent the longer the project dragged on, made me angry. These were the days where I fruitlessly attempted to solve programming problems above my pay grade. These were the days where a playtester made a reasonable and compelling case to overhaul something that had been completely fine and final for months. These were the days where I sacrificed all my free time to work on this game, for the sake of a release deadline that was always "next month" no matter how much I worked. I took a week of vacation in the summer of 2017, and about the only thing I remember is being glued to my computer for 10+ hours a day in a futile attempt to finish the game that month.

When I set the official release date, I was in a weird place. My need to retake control of my life finally outweighed my desire for the game to be as polished as possible upon release. I knew there were glitches to fix, challenges to playtest more thoroughly, details to streamline, and features to add, but all the most important stuff was in place and reasonably solid. I was happy with it. The game was playable from start to finish. The majority of playtesters enjoyed the game. OH JOES! was more release-worthy than many other fangames I'd played. It was time to hand the game over to the largest group of playtesters yet, take a break, and come back fresh when there was a consensus about what I should focus on for the next update.

The plan for OH JOES! was a soft launch, announcing the game on Twitter, Facebook, Discord, and Sprites INC, where I'd been posting about it during development. It made sense to debut to a smaller audience who knew what to expect, and who was maybe even looking forward to the game. After a week or two of incorporating feedback from the general public, I'd "officially" announce the game on YouTube (to around 12,000 subscribers between both my channels) and on the forums at Capcom Unity, Rockman Perfect Memories, Cutstuff, Talkhaus, and anywhere else I could think of.

Despite all the headaches and hurdles, I was about to fulfill a childhood dream. I was nervous but optimistic, relieved but excited. I created a page on this website with information about the game, put together a download package, and played through the game one last time. I uploaded the game to three different file-sharing sites (always have a backup!) and tested that each download worked correctly. Then, I took a deep breath and announced my dream to the world.

It took the world 20 minutes to trample my dream, spit on it, and toss the pieces in my face.

I've been a content creator long enough to know that not everything I produce will be an instant hit with the public. I'm always braced for some measure of criticism, and I've learned to brace myself even more when it comes to level design. I was wholly unprepared for the hostility, ridicule, and indifference my game was about to receive, and I was blindsided by the things people would choose to complain about.

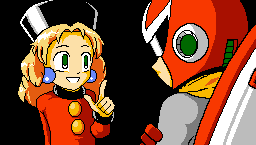

First was that initial ripple of excitement—hey, the game's finally out, congratulations, I can't wait to play it. Next were the first impressions—that cutscene art is fantastic; this music is great. So far, so good. Then came the bug reports—or more accurately, the memes making fun of the shoddy game engine, my horrible programming, and the apparent lack of playtesting. People were getting stuck in walls and crashing the game before even making it to the first checkpoint. Multiple people were outraged by the framerate, as though 30 FPS (more or less the fangame standard until OH JOES! was well underway) was utterly unplayable. Whatever credibility I had as a developer was gone before anyone got to the actual gameplay, by which point OH JOES! was just another no-effort fangame for people to trash. Notwithstanding the remarks about the art and music, the most positive thing I saw anyone say on Discord was that the game overall was "meh."

What a profound waste of my life this game was.

I had to walk away from my computer. I felt sick. What had been a source of tremendous joy and pride 20 minutes prior had rapidly turned into a painful mistake. One might argue that I was being overly sensitive to criticism, interpreting comments as negative when they weren't intended as such. But over the next four months, social media only reinforced the notion that nobody actually liked OH JOES!.

People complained about the lack of infinite lives, the fact that Proto Man loses his charge when hit, and the fact that a couple items require a specific character or weapon to collect—so I was being criticized for staying true to the official Mega Man games. But then people complained about the lack of a stage select or "real" final boss—so I was also being criticized for deviating from the official Mega Man games. I heard that the game was both too easy and too hard, that there were too many power-ups and not nearly enough, and that the game overstayed its welcome but wasn't long enough. There was no shortage of conflicting feedback from the general public.

But it didn't stop there. The lack of original Joes (when the entire point of the game was using tired old Joes in new situations) was disappointing to people. Over 250 screens of challenges, and the game did nothing new or interesting with Joes. Three meaningfully different difficulties, three meaningfully different characters, and a large degree of control over which challenges you face and how to face them, yet the replay value came across as artificial. How was I supposed to work with this feedback? These weren't critiques I could use to improve the game; these were indications that my game was a lost cause.

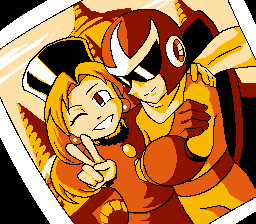

I'm better at handling the negative when there's some positive to focus on, but there was a gut-wrenching absence of praise for the story, dialogue, level design, tile work, special features, overall execution, and anything else I was responsible for. The only things people seemed to like were the stage music (of course, because Cosmic, Jasper, MiniMacro, and RushJet1 are extremely talented), cutscene art (of course, because Phusion is amazing), and secret character (of course, because she's a silly surprise who completely changes the gameplay nobody was enjoying). A handful of people involved in the project, who had previously stated that they liked the game, reiterated that they still liked it. I appreciated their support, but I also wanted—needed—some affirmation from the general public.

To give some numeric perspective: My initial announcement on Discord, Facebook, and Twitter reached a minimum of almost 600 different people—and depending on how much overlap there was between subscribers across the different platforms, that number could have been as high as 1500. I haven't been able to track the number of downloads from Dropbox and Google Drive, but MediaFire tells me that OH JOES! has been downloaded over 400 times—and I'm not sure whether that's since release, or just since I uploaded the last update. The first playthrough of the game that anyone posted on YouTube had over 1000 views within a few months of release, and my post about the game on Sprites INC had over 30,000 views. Even if, say, 90% of those views were repeat visitors and not unique views, those are still significant numbers.

In short: there were hundreds, if not thousands, if not tens of thousands of people outside the development team who knew about OH JOES!. Of these, five people in as many months said anything to make me feel like I wasn't a total failure as a game designer. With the exception of one glowing and articulate review, the praise was concise and tempered: the game was fun, despite [insert shortcoming]. Meanwhile, I continued seeing hostility, disappointment, and indifference toward the game every day, then every few days, then every week, until people stopped talking about it altogether. Whenever I brought up the game's unpopularity in conversation, secretly hoping that someone would chime in with something nice to say, the response was invariably, "Oh, that's too bad." Pity felt almost like an acknowledgment that there was nothing nice to say. Even on the rare occasion when someone tried to defend my game against criticism, their response was usually something to the effect of, "Well, the problem isn't that bad...".

Emotionally, I was extremely unwell for several weeks after the game's release. There's a sickening bitterness that arises from being so proud of something—something that you devoted years to creating, that other people told you they liked—and then having your self-worth pounded into oblivion when you put your creation on display. After a few days, I no longer had the drive to record an announcement for YouTube. After a week, I was this close to deleting the game's page from my website and killing the download links. After two weeks, I nearly stepped down as a judge for Make a Good Mega Man Level Contest 3. I felt like the game's existence was ruining my reputation in the fan community, and I wanted nothing more to do with it.

The game's few vocal supporters eventually convinced me that maybe, somehow, the game hadn't reached the right audience yet. I worked up the energy to advertise the game on a couple small gaming forums, but by that point, the branding was substantially different. "I'm excited to share my game with you" had changed to "Here's this thing I made; maybe it's not a total waste." The only response I've received on any of those forums is a compliment about the cutscene art. I made an effort to review bug reports and update the game if anything critical came up, but I expended a minimum amount of effort in implementing any changes. I also started writing this series of blog posts—partially for posterity, partially to share some insights about what it's like to design a game, but mostly to try to salvage the memory of this deeply personal project.

I didn't spend two years making a game; I spent two years on a challenging, emotional, eye-opening journey to fulfill a dream I've had since childhood. Looking back on the high points, I can be proud of what I accomplished and happy with the personal relationships that developed along the way. Looking back on the low points, OH JOES! caused me an unprecedented amount of stress and suffering for something that was supposed to be fun. If I could go back and do it all over again...I wouldn't.

I think about how eager I was to make more Mega Man levels, and how I would have gotten my fix if I had just waited a few months for Make a Good Mega Man Level Contest 2 and then a few more months for Mega Man Maker to arrive. I think about how many YouTube videos I could have recorded in the time it took to make OH JOES!—and how much happier both I and my content-starved audience would have been. Most of all, I think about how much it hurt to spend two years crafting a keen blade intended to cut through an afternoon of boredom, only to have my peers use it to carve out my heart.

But hey, at least I got some blog posts out of it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed