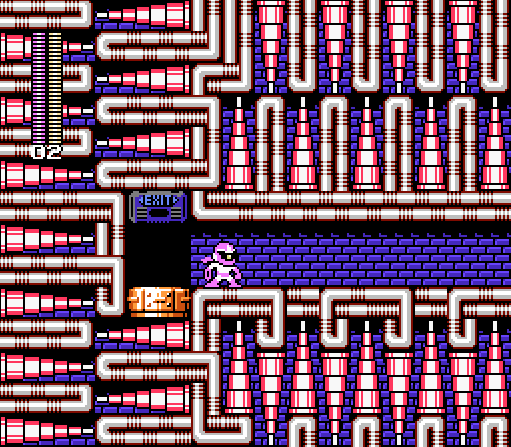

The Make a Good Mega Man Level Contest (MaGMML) 3 judge team was assembled a full year before judging began. We had plenty to keep us busy in that time, but I took on some non-judge work as well.

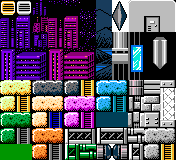

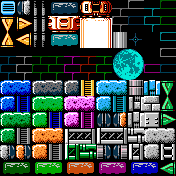

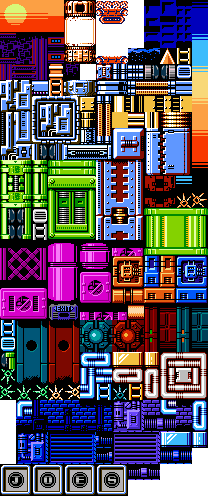

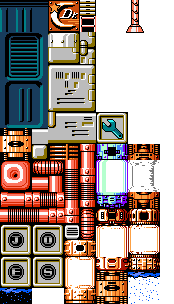

I spent a good chunk of 2018 helping to expand and test the game engine, making such contributions as assembling new tilesets (eg, the MM10 lab), reorganizing existing tilesets and creating slopes for some of them (eg, Skull Man; Charge Man; MM1 Wily 1, 2, and 4; MM2 Wily 1), and checking engine assets for fidelity to the original games (eg, all the Joes). For a time, I also was in charge of showcase development—that is, planning, building, and delegating the example levels that show off everything available in the engine.

I knew that contestants would be influenced to some degree by how the engine assets were presented to them. Without a showcase, many people would stick with the gimmicks and enemies they were familiar with, and overlook a lot of the engine's customization options. At the same time, any kind of showcase ran the risk of encouraging contestants to crib from the example levels—whether due to a lack of creativity, a false assumption that the example levels demonstrated the "right" way to use these assets, or a genuine inspiration to develop one of the sample challenges into a full level.

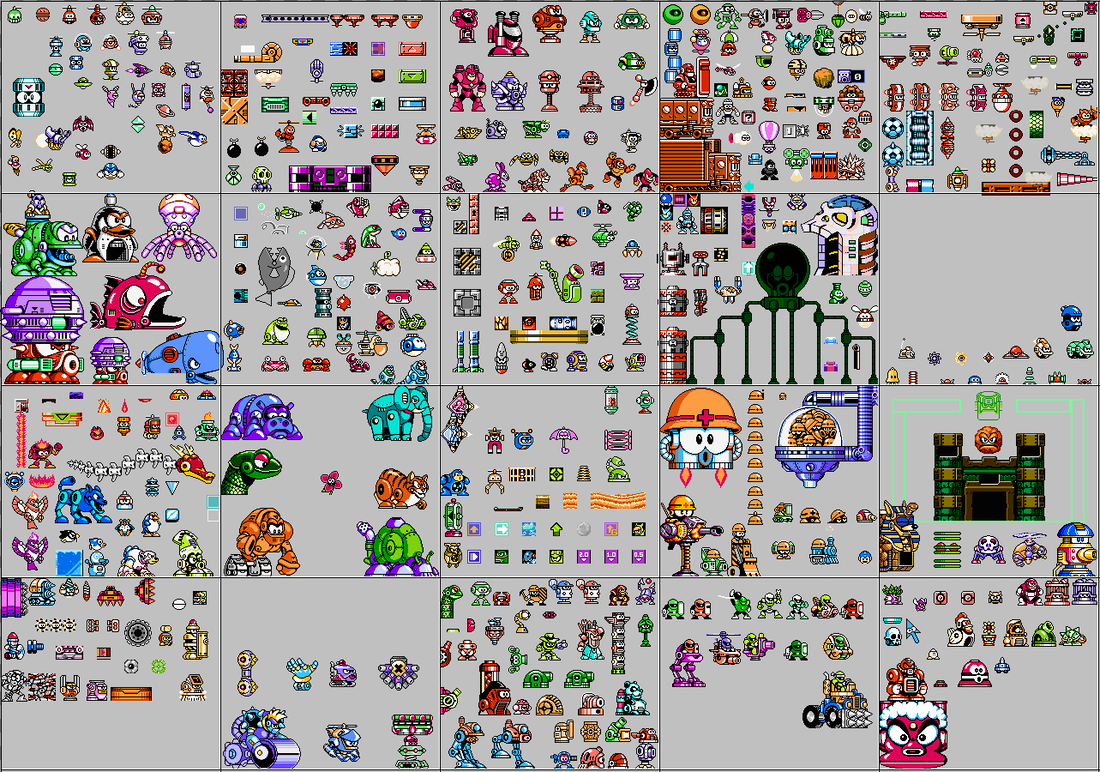

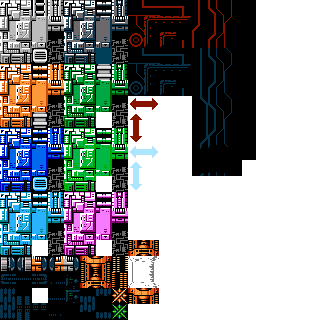

Before I took over showcase development, the team was grouping assets together by stage—here's everything from Cut Man, here's everything from Heat Man, and so forth. My main objection to this approach was that it would reinforce that certain assets need to go together, because that's how they appeared in the original games. After a lot of discussion, we agreed to rework everything and break up the assets by theme and/or function. I created a blank room in GameMaker; inserted one instance each of every enemy, gimmick, miniboss, and boss in the engine; and then started organizing these assets into categories (eg, water minibosses, moving platforms). Not unlike dumping out a basket of clothes and sorting them into piles.

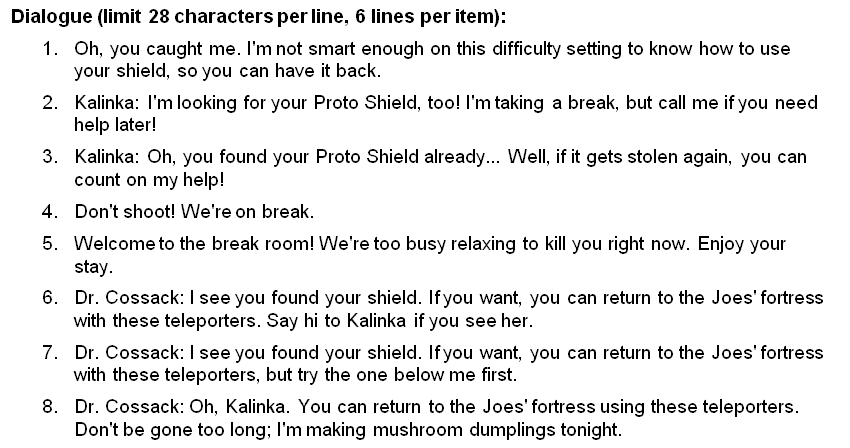

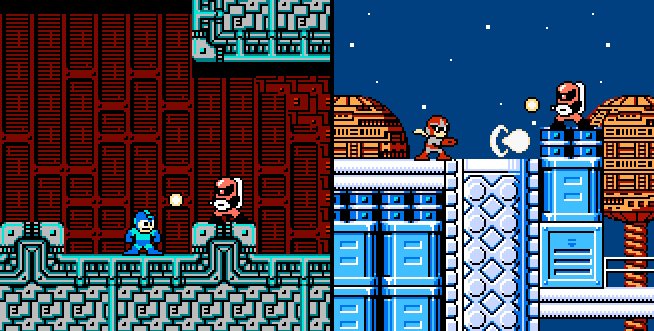

- Showcases should demonstrate as much potential as possible for each asset—things you can do with the creation code (eg, color variations), unique interactions with other assets (eg, lighting oil on fire), any functionality that isn't immediately obvious (eg, totem poles jumping when the player passes over them), etc.

- In general, try to introduce only 1-2 new assets per screen, so as not to overwhelm and distract the player; more assets can be introduced together if they share very similar functionality (eg, one screen with four variations of Shield Attacker is totally fine).

- Avoid using enemies and gimmicks that are showcased elsewhere; a little overlap is OK if necessary.

- Give the player frequent checkpoints and power-ups, and keep instant death to a minimum; the purpose is to give the player inspiration, not a hard time.

- No split paths or secret areas, please. Players should be able to go through the showcase once, see everything, and move on to the next showcase. If you feel your showcase is getting too long, let me know and we'll look at moving some assets into a new/different showcase.

- Leave a few screens' worth of open space on all sides of your showcase, in case more assets need to be added later.

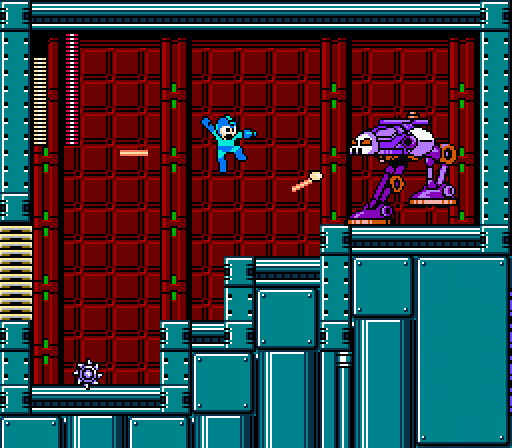

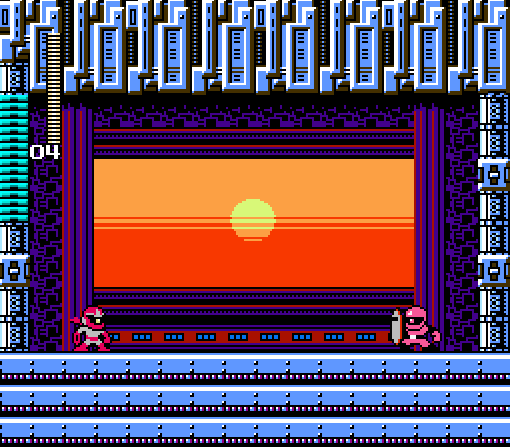

- Use placeholder graphics until your level is finished and has been playtested. Once the design is more or less finalized, THEN decorate your level using the default tilesets included in the devkit. Try to limit yourself to just one tileset if at all possible, and keep the design simple. For the sake of time, consistency, and clarity, the focus should be on the assets; save your artistic skill for the actual contest.

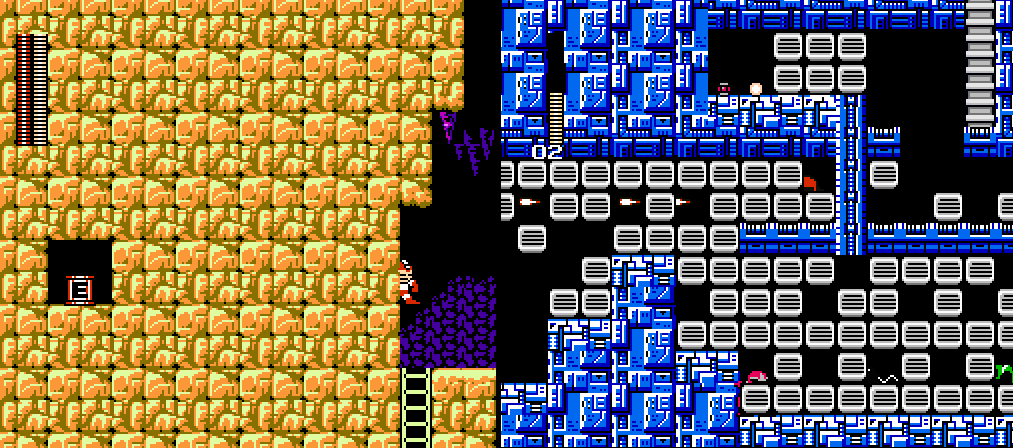

- A Slog of Ice and Fire

- A Torrent of Turrets

- Airborne Assailants

- Brawl of the Wild

- Castle Castoffs

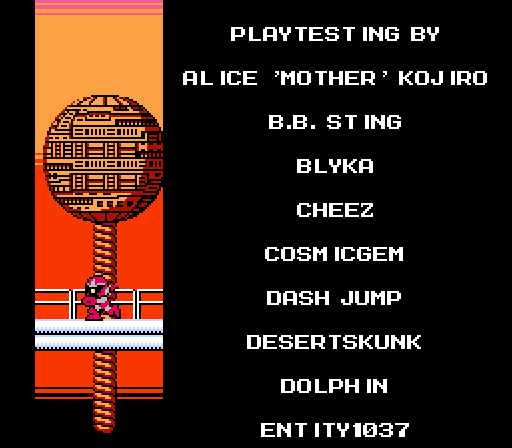

- Circuit Breaker

- Demolition Mission

- Extraordinary Ordinance

- Factory Fisticuffs

- Fan the Flame

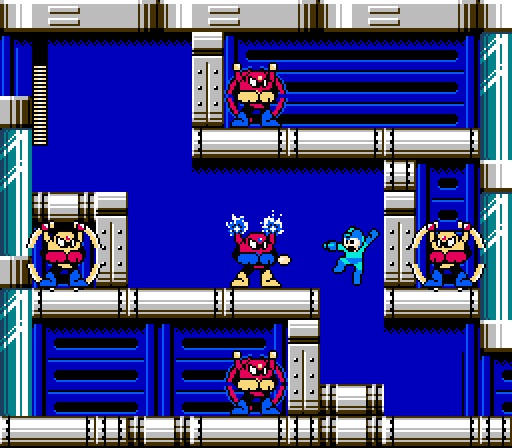

- Fluidic Foes

- Ground Control

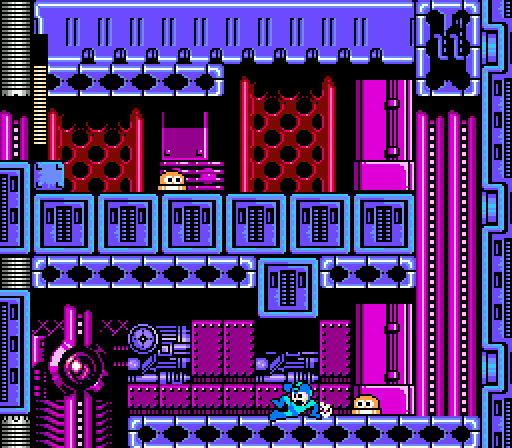

- Industrial Intrigue

- Invite Your Fiends

- Landlocked Leftovers

- Maniacal Manipulators

- Might As Well Jump

- Misfit Minibosses

- Modified Mobility

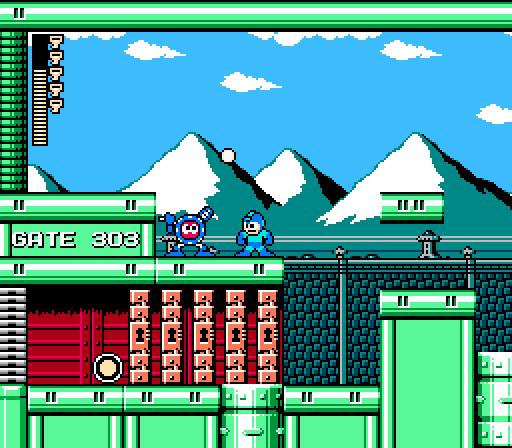

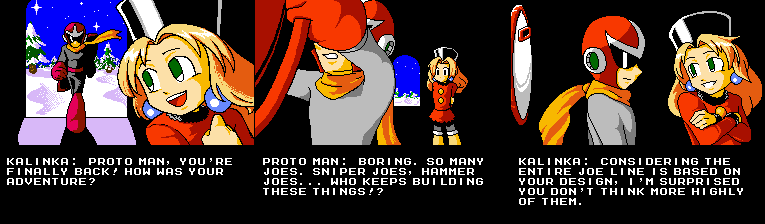

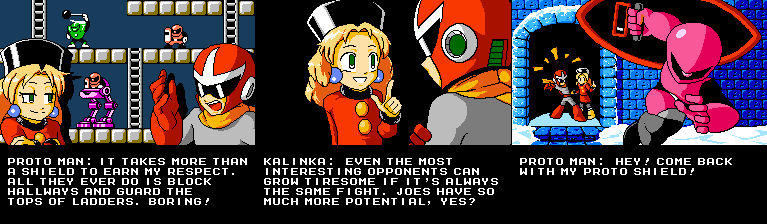

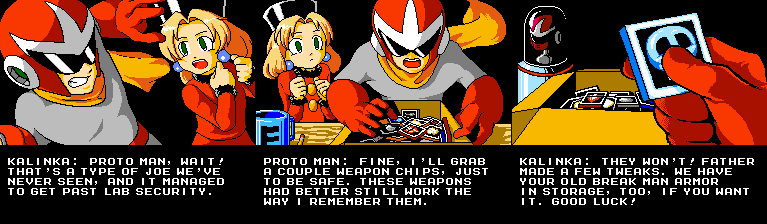

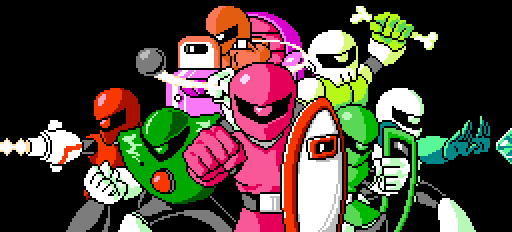

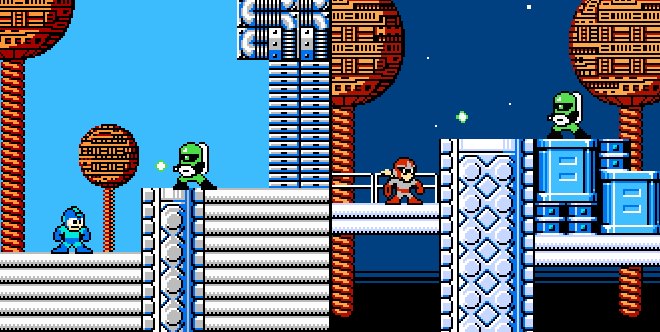

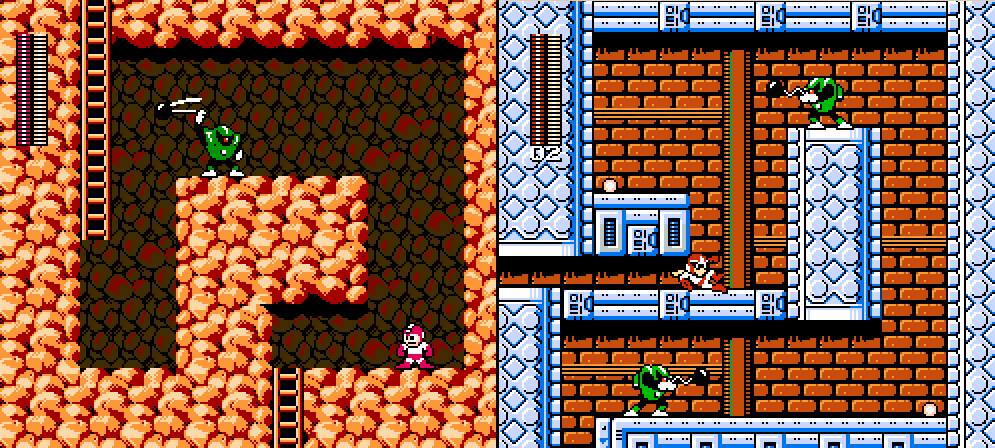

- Never Gonna Let You Joe

- Perilous Patrol

- Platform Swarm

- Pleased to Met You

- Razor-Sharp Rivals

- Respect the Unexpected

- Spectacular Spawners

- Submerged Scuffle

- Thug Zappers

- Water You Doing

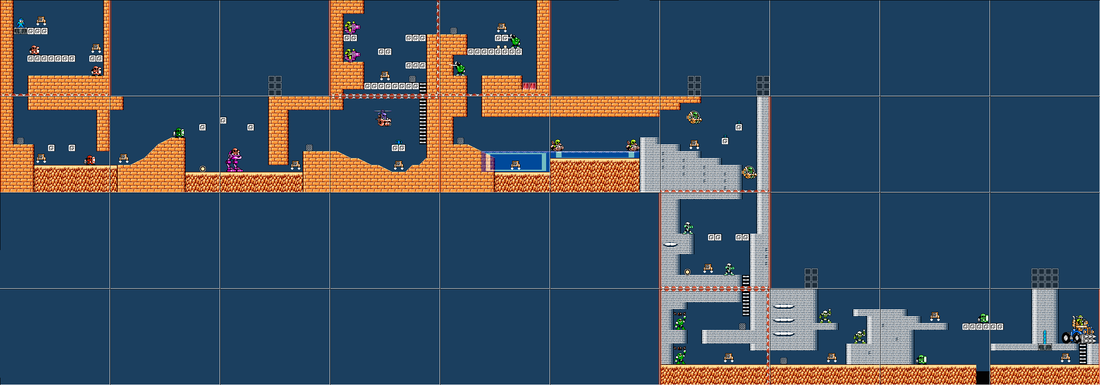

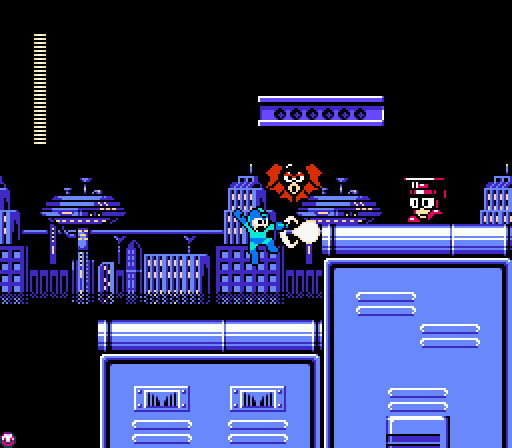

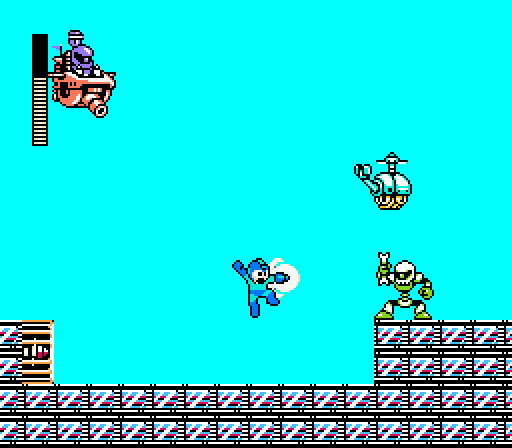

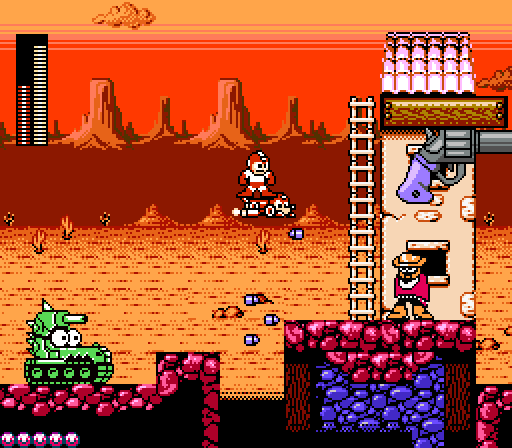

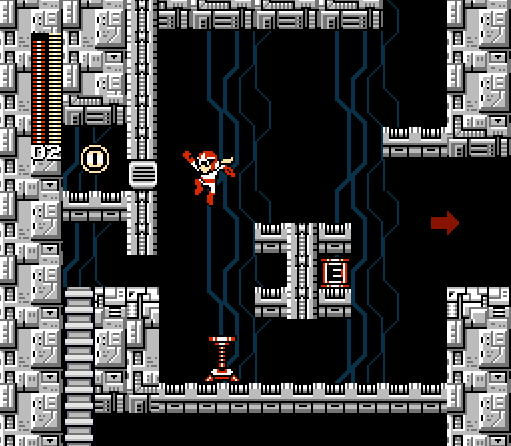

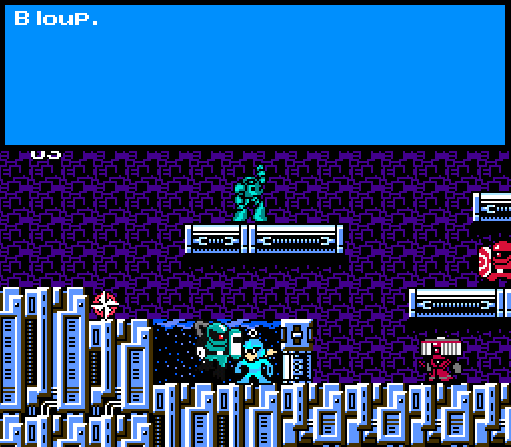

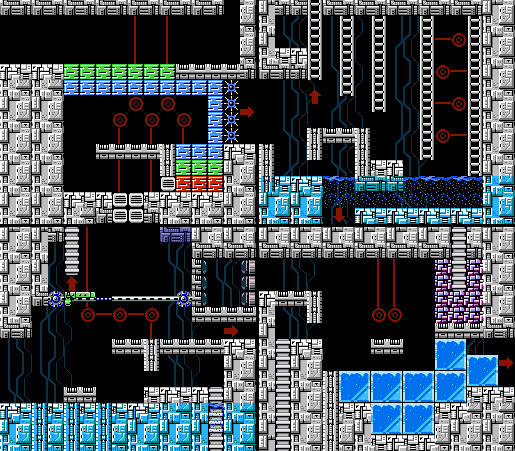

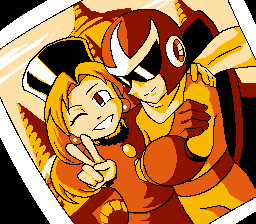

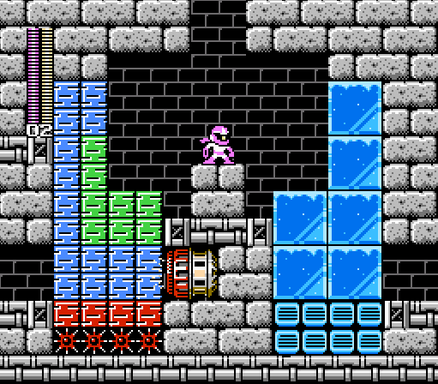

I called dibs on Maniacal Manipulators (bosses with physics-altering attacks, one of whom is Flash Man, my judge avatar for the contest), Landlocked Leftovers (all the ground-based enemies that didn't fit anywhere else), and Never Gonna Let You Joe. After devoting two years of my life to OH JOES!, a game devoted to using this tired old enemy type in new and different ways, there was no way I wasn't going to claim the all-Joe showcase (Joecase?). Although I wouldn't consider it one of my strongest levels, I relished the self-imposed challenge of making the level beatable without destroying a single Joe (seriously, try it). Plus, I got to put some of my custom slope tiles to use.

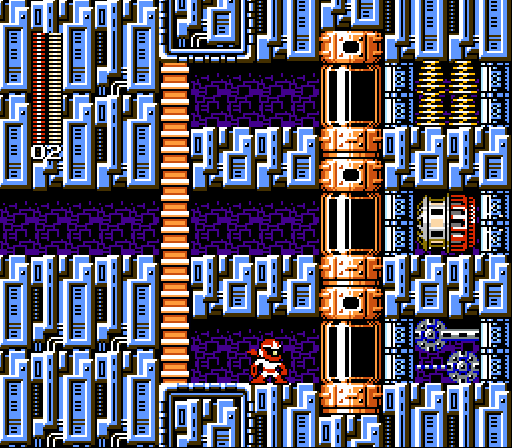

The sheer size of the devkit meant absurd amounts of time spent loading and compiling in GameMaker. With OH JOES!, I could fire up the software, make a change, test it, tweak it, and test it again in a matter of minutes; with the MaGMML3 devkit, the same amount of work could easily take half an hour. Level design was suddenly an arduous, inefficient task that required me to plan my time differently and adjust how I approached playtesting.

Moreover, the showcase was being designed while the engine was still being expanded and tested. From a programming perspective, it's incredibly helpful to see how assets behave in normal gameplay situations. From a level design perspective, it's difficult to plan out challenges when the building blocks are still being finessed. I spent a lot of time logging issues on GitHub or, in rare cases, attempting to make programming changes myself. To push my changes to the rest of the devteam, I had to learn to use a command-based software called Git Bash. Even with a comprehensive guide from devteam member NaOH, I frequently ran into confusing, infuriating issues (read: merge conflicts). All I wanted to do was design some levels.

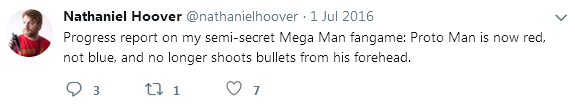

Recognizing that I needed to step back, I passed the torch to devteam member CWU01P, who did a terrific job of picking up the slack. Really, the whole devteam did some impressive work in pulling together the showcase.

If you'd like to take the showcase for a spin, it's packaged with Megamix Engine, which you can download here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed